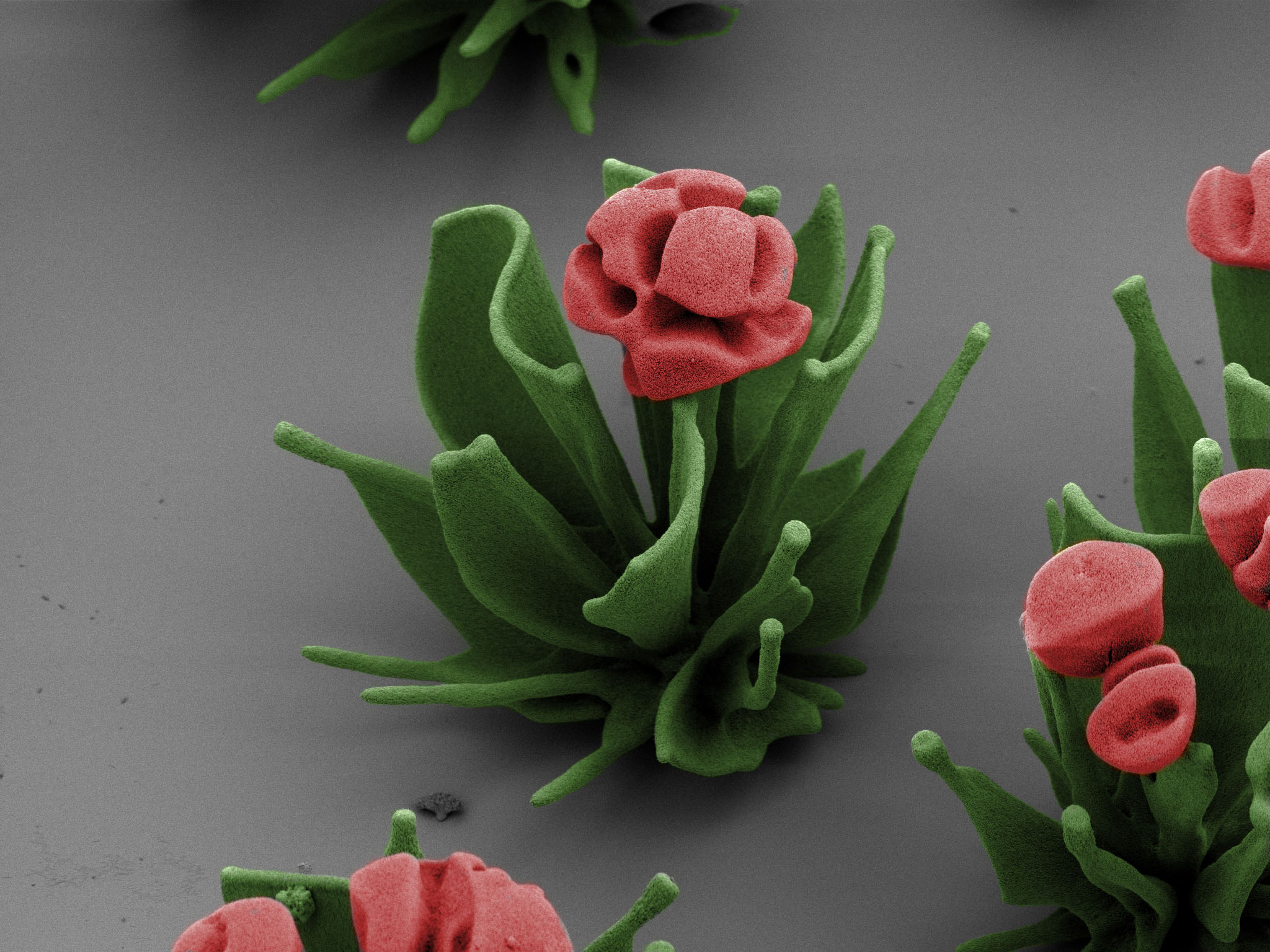

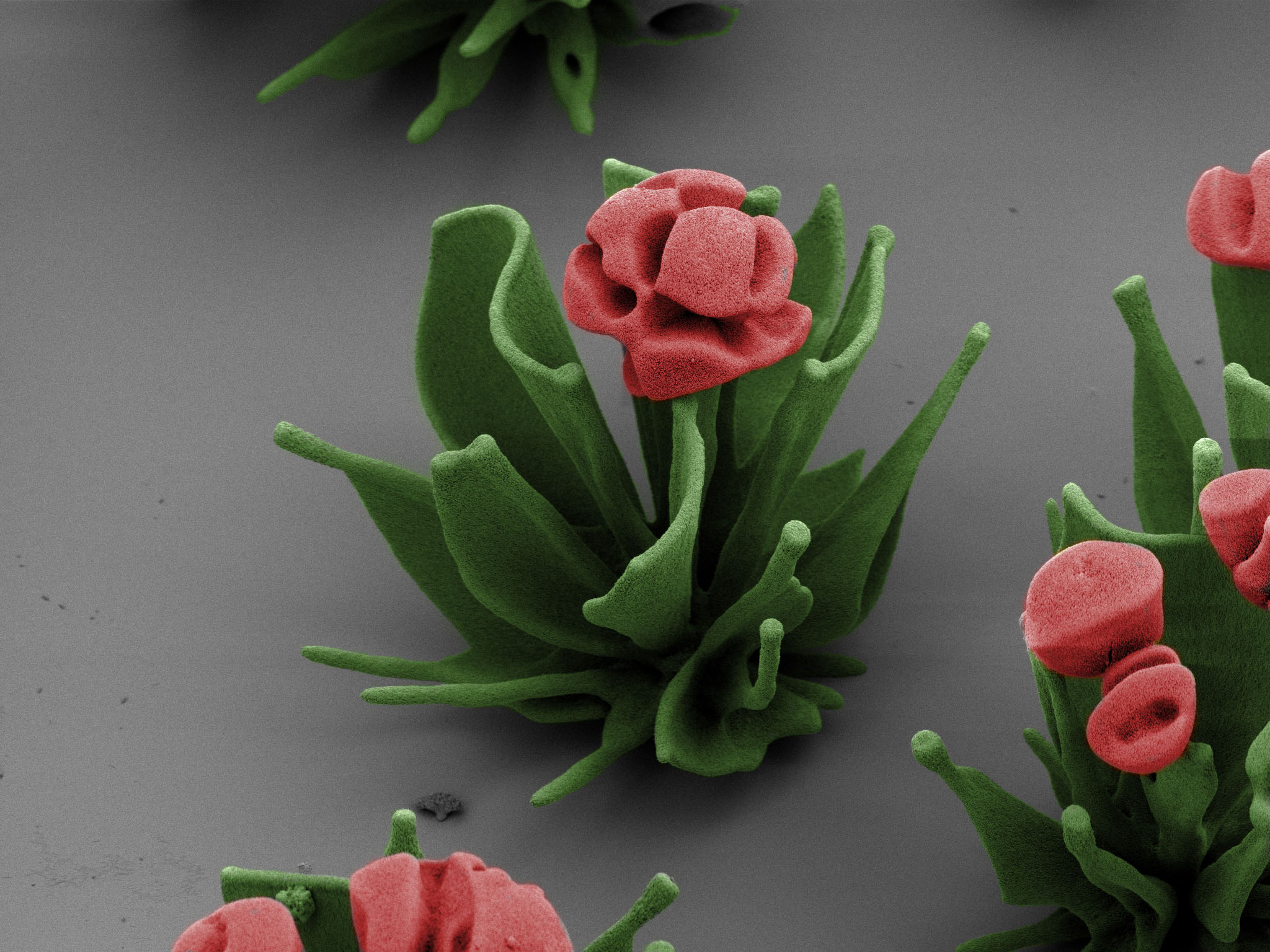

Part of being human means living with the understanding that, sometimes, seeing isn't the only route to believing. For centuries, scientists have battled the nebulous challenges presented by the invisible through rigorous experiments of exponentially shrinking scale. It is exactly this cat-and-mouse game of conquest that has provided many of the fundaments upon which modern science rests. In order to discover cells, for example, both scientists Robert Hooke and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek constructed their own microscopes to seek out these tiny universes. Similarly, in order to examine the worlds of bacteria and microbes, in 1931, German physicists Max Knoll and Ernst Ruska constructed the first prototype of the electron microscope.Today, science is pushing the limits of what we can and cannot see, by not only using the electron microscope to its fullest potentials, but creating art beneath it. Using combinations of chemicals, refined lab techniques, and the finest in optical technologies, two Harvard scientists have begun creating intricate crystalline structures that look quite a bit like delicate, organic flower blossoms.For our documentary on crystal nano flowers, we sat down with Harvard University postdoctoral research fellow and effective chemio-"botanist," Wim Noorduin, and Harvard chemistry professor Joanna Aizenberg."Over the last three years, I've been looking at ways to grow micro-sized structures by manipulating the surrounding conditions. In this research, I learned how to combine chemistry to sculpt crystal while it's growing," Noorduin told The Creators Project, in our documentary, viewable above. "I think it's a fundamental goal to try to understand how you can make structures with such a complexity at a really small length-scale. And from that point, only a few will be starting to understand a little bit [about] how nature makes all these fascinating structures."Below, Noorduin's lab-grown, Secret Garden-worthy creations:

It's quite literally an effort in making somethings out of nothing. "Every structure is maybe the diameter of a hair […] The crystals are so small and held together by this amorphous material that you can basically make any arbitrary shape.""To grow the structures, we mix together two starting materials," Noorduin explained. "Basically, as soon as I do that, the reaction starts and then we wait for two hours. We now can really use these chemical reactions to make any kind of arbitrary shape we want, and the fact that you already can grow such a flower in two hours really allows you to do a lot of experiments and learn a lot in a very fast manner.""Over the years, I've been growing thousands of these samples, and I've tried many ways to stack structures on top of each other, and to sculpt them while they're growing," Noorduin continues, referring to his trial-and-error process of mixing crystallizing chemicals. "I notice, of course, that with all these experiments, some things aesthetically simply work better than others. That's how I started to develop a sort of style in which most of the structures started to look like flowers."For Noorduin and company, these developments in nano-crystal architecture have posed unparalleled new questions for both chemists, physicists, and engineers to ponder. "Can you really write a message in morse code on a flower?" he asks. "Can I place a coral exactly on top of a stem? For me it's really about finding the boundaries, controlling the system, and growing exciting structures."

It's quite literally an effort in making somethings out of nothing. "Every structure is maybe the diameter of a hair […] The crystals are so small and held together by this amorphous material that you can basically make any arbitrary shape.""To grow the structures, we mix together two starting materials," Noorduin explained. "Basically, as soon as I do that, the reaction starts and then we wait for two hours. We now can really use these chemical reactions to make any kind of arbitrary shape we want, and the fact that you already can grow such a flower in two hours really allows you to do a lot of experiments and learn a lot in a very fast manner.""Over the years, I've been growing thousands of these samples, and I've tried many ways to stack structures on top of each other, and to sculpt them while they're growing," Noorduin continues, referring to his trial-and-error process of mixing crystallizing chemicals. "I notice, of course, that with all these experiments, some things aesthetically simply work better than others. That's how I started to develop a sort of style in which most of the structures started to look like flowers."For Noorduin and company, these developments in nano-crystal architecture have posed unparalleled new questions for both chemists, physicists, and engineers to ponder. "Can you really write a message in morse code on a flower?" he asks. "Can I place a coral exactly on top of a stem? For me it's really about finding the boundaries, controlling the system, and growing exciting structures."

The Creators Project also spoke to Joanna Aizenberg, a professor of chemistry at Harvard University, and one of Noorduin's greatest supporters. On the importance of Noorduin's crystal nano flowers, Aizenberg said: "Basic science is critical. We do need to understand how and why things assemble. How and why the emergence of form leads to certain structures. Without this basic understanding, we won't be ever able to professionally design the structures, materials, and complex systems that we can use in the future devices."Aizenberg went on to wax poetic on why it's important that these tiny structures are not only scientifically sound, but artistically:The interesting feature of this interaction was a consideration for beauty, a consideration of artistic value. If we're designing new structures, new materials are absolutely critical to think about their aesthetic appearance. […] We use this as a model system. It doesn't have to be these materials. It's just the simplicity of that combination that will help us understand the emergence of form, the emergence of curvature, the emergence of complex hierarchical architectures. Imagine: lab-grown sculptures with the individual complexity of a fingerprint. We've seen castles etched on a grain of sand, but flowers on the face of a coin?

The Creators Project also spoke to Joanna Aizenberg, a professor of chemistry at Harvard University, and one of Noorduin's greatest supporters. On the importance of Noorduin's crystal nano flowers, Aizenberg said: "Basic science is critical. We do need to understand how and why things assemble. How and why the emergence of form leads to certain structures. Without this basic understanding, we won't be ever able to professionally design the structures, materials, and complex systems that we can use in the future devices."Aizenberg went on to wax poetic on why it's important that these tiny structures are not only scientifically sound, but artistically:The interesting feature of this interaction was a consideration for beauty, a consideration of artistic value. If we're designing new structures, new materials are absolutely critical to think about their aesthetic appearance. […] We use this as a model system. It doesn't have to be these materials. It's just the simplicity of that combination that will help us understand the emergence of form, the emergence of curvature, the emergence of complex hierarchical architectures. Imagine: lab-grown sculptures with the individual complexity of a fingerprint. We've seen castles etched on a grain of sand, but flowers on the face of a coin?

There's also much to be said for the accessibility of his recently developed procedure. "A lot of great science is done with very expensive equipment. I think one of the nice things about this research is that you can use two very cheap chemicals, and throw them together, and already really do science. I think that really shows that it can be approachable." So what's next, growing crystal nano kits for kids?Maybe, but Noorduin has to stop enjoying his research so much, first. "For 3 years now, I've been looking at these very strange white stripes on plates that are maybe only an inch long or so. And every time I'm amazed that it's a complete sort of coral reef that you're diving into as soon as you look under the microscope," he fondly recalled. "I notice quite often that I simply forget to make photos because I just want to look further and further on the samples and discover new structures and then get lost. These small samples really contain their own world."How have these delicate micro-artworks been received? "The feedback is very broad. Of course, there are many scientists that find this work interesting, but also just people from all over the world who are intrigued by the shapes; especially when you consider that these images were for about three years only on my computer, and then suddenly in one day they are all over the internet— that is very strange to me. " One look beneath the electron microscope, however, and the reasons for the successes of this project become clear as crystal.As a special treat from Noorduin, put on your red-and-blue glasses and enjoy some 3D Crystal Nano Flowers:

There's also much to be said for the accessibility of his recently developed procedure. "A lot of great science is done with very expensive equipment. I think one of the nice things about this research is that you can use two very cheap chemicals, and throw them together, and already really do science. I think that really shows that it can be approachable." So what's next, growing crystal nano kits for kids?Maybe, but Noorduin has to stop enjoying his research so much, first. "For 3 years now, I've been looking at these very strange white stripes on plates that are maybe only an inch long or so. And every time I'm amazed that it's a complete sort of coral reef that you're diving into as soon as you look under the microscope," he fondly recalled. "I notice quite often that I simply forget to make photos because I just want to look further and further on the samples and discover new structures and then get lost. These small samples really contain their own world."How have these delicate micro-artworks been received? "The feedback is very broad. Of course, there are many scientists that find this work interesting, but also just people from all over the world who are intrigued by the shapes; especially when you consider that these images were for about three years only on my computer, and then suddenly in one day they are all over the internet— that is very strange to me. " One look beneath the electron microscope, however, and the reasons for the successes of this project become clear as crystal.As a special treat from Noorduin, put on your red-and-blue glasses and enjoy some 3D Crystal Nano Flowers: Images courtesy of the artistsRelated:[Exclusive Video] Creating Sand Castles With A Single Grain Of SandExplore A World Of Micro-Cities And Neon Furniture At "Glimpses"Intricate Digital Collage Turns Chinese Landscape Into Sprawling Wonderland

Images courtesy of the artistsRelated:[Exclusive Video] Creating Sand Castles With A Single Grain Of SandExplore A World Of Micro-Cities And Neon Furniture At "Glimpses"Intricate Digital Collage Turns Chinese Landscape Into Sprawling Wonderland

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement